#

Comparison

We explain how smart contract systems for Bitcoin work in simple terms. We then compare the Bitcoin Computer to other systems according to the following properties:

- Trustlessness. We call a system trustless if no trusted third party is required for its operation. Trustlessness is the main point of the entire crypto endeavour as Satoshi pointed out in the second sentence of the Bitcoin white paper: "the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required".

- Expressiveness. A system is expressive if it can express all computable smart contracts, formally if it is Turing Complete. Assets created in such general purpose protocols can be freely composed and moved between applications.

- Efficiency. A system is efficient if it is possible to compute some smart contract data without having to parse all transactions in the blockchain. This is important for two reasons: the obvious one is that it is faster to compute some values. The other is that it is possible to compute values in parallel.

#

Results

The table below captures the results of our comparison. Each result is explained in detail in the following sections.

#

Blockchains

For context we briefly discuss to what extent Bitcoin and Ethereum have the three properties we are interested in.

#

Bitcoin

Bitcoin is a trustless peer-to-peer currency. We will assume familiarity with the basic working of Bitcoin and focus on the three properties from above.

Bitcoin is assumed to be trustless as long as a majority of the hash power is honest. However it is not expressive as it only supports one application: a currency. It is also not efficient as one needs to validate all transactions and check the proof of work of every block in order to determine if the amount in an output is unspent and the transaction containing the output is valid.

#

Ethereum

Ethereum is the first blockchain to popularize general purpose smart contracts. It assumed to be trustless as longs as a majority of the staked cryptocurrency is owned by honest validators. In addition it is expressive due to its native smart contract support. However, it is not efficient: to determine the storage of one address, a full node needs to synchronize with the entire blockchain, validating all transactions and computing all smart contract invocations.

#

State Channels and Networks

State channels, originally designed to reduce fees, have recently found applications in smart contract systems. They allow two parties to conduct transactions off-chain with only the final agreed-upon state recorded on the blockchain. Two parties can send payments back and forth an unlimited number of times at a constant cost. However the fee reduction is less pronounced for unidirectional payments.

While state channels work well between two users, they do not scale to a large number of users, because creating channels between all users quickly becomes uneconomical. To address this shortcoming, channel networks have been developed. These use smart contracts called Hashed-Timelock-Contracts (HTLCs) to create chains of channels that securely forward payments, ensuring that intermediate nodes cannot steal funds. This enables efficient hub-and-spoke architectures where a central hub forwards payments between users. One downside is the existence of a central point of failure in the form of the hub; another is that users need to be online to receive payments securely.

#

Examples

The Lightning Network extends the hub-and-spoke model to a decentralized network of payment channels. The key challenge is to solve the routing problem: to send a payment between two users, a path of channels must be determined where each channel has sufficient liquidity to forward the payment. To determine such a path, users must have up to date knowledge of the balances of all channels. If a user's knowledge of channel balances is outdated, the payment can fail.

Watchtowers allow users to accept payments whilst offline. These are third party services that monitor end users' channels for suspicious activity and react accordingly. The downside is that this introduces a trusted third party. More info

The ARK protocol is a layer-two solution designed for off-chain Bitcoin transactions, aiming to provide a low-cost, setup-free payment system. ARK relies on trusted intermediaries called ARK Service Providers (ASPs) to manage shared UTXOs. In ARK, transactions are conducted using virtual UTXOs (VTXOs), which are off-chain transaction outputs that can be converted into on-chain UTXOs when needed. Payments within ARK are coordinated by the ASPs through periodic "rounds," where users exchange their VTXOs for new ones off-chain. Additionally, ARK offers "out-of-round" payments for faster, direct transactions between parties. More info

The RGB protocol enables smart contracts. All meta data is stored offline, which lowers availability guarantees. RGB uses transaction outputs as "single-use seals" that ensure that only the owner can modify the contract state. RGB uses specially-designed virtual machine called AluVM, which is is nearly computationally universal, but with a bounded by number of operation steps, similar to in Ethereum-like systems. RGB has support for for enhanced privacy via a modified form of confidential transactions. RGB can operate over regular Bitcoin transactions and over the lightning network. More info

The Bitcoin Computer currently does not support channels networks. However we mention it here as an integration could be built in principal. The Bitcoin Computer will be further discussed

#

Evaluation

Trustlessness. State channels and networks are trustless as long as users are online. When users are not online they need to trust watchtowers to keep user funds safe. Smart contract systems that rely on channel networks inherit these properties.

Expressiveness. Most channel networks are geared towards payments, therefor they cannot express smart contracts. However some smart contract protocols can integrate with state channels, in which case all smart contracts of the respective protocol can be expressed.

Efficiency. Our definition of efficiency only makes sense for smart contract systems, so this property does not apply to payment networks.

#

Interoperable Blockchains

An interoperable blockchain is a separate blockchain that connects to Bitcoin in various ways. In most cases smart contracts of the interoperable blockchain can read and write transaction from and to Bitcoin. In some cases, Bitcoin is used in the consensus of the interoperable blockchain.

#

Examples

Stacks enables smart contracts that use Bitcoin as an asset in a trust-minimized way. It has its own native asset called STX. The Stacks blockchain relies on STX and BTC for its consensus mechanism called Proof of Transfer (PoX). Stacks miners bid by spending BTC, and their probability of mining the next block on the STX chain is proportional to the amount bid. This amount is paid to STX holders that lock up or "stack" their STX. As a consequence the price ratio between BTC and STX is continually recorded and available on-chain. Stacks's smart contract language is a non-Turing complete language called Clarity. More info

Todo. More info

#

Evaluation

Trustlessness. Interoperable blockchains are as trustless as the blockchain that is connected to Bitcoin.

Expressiveness. Typically, all smart contract systems can be expressed.

Efficiency. Interoperable blockchains that support smart contracts are typically based on the account model like Ethereum and are therefore not efficient.

#

Sidechains

A sidechain is a separate blockchain linked to Bitcoin through a two-way peg.

A user sends their Bitcoin to a dedicated address controlled by the group of users that maintain the peg. These users then create the corresponding value of tokens on the sidechain. Those tokens can be used to access the functionality of the sidechain. Later, the sidechain user can transfer tokens back to the maintainers the peg, who will hopefully send the corresponding amount of tokens back to the sidechain user.

Two-way pegs can be centralized, federation-based, or SPV-based. In centralized two-way pegs a trusted third party controls the Bitcoin in the peg and is responsible for locking and unlocking the Bitcoin. In a federated peg, the locked Bitcoins are at the custody of a group of users called the federation. A common implementation is to use a multisignature address, in which a quorum of participants is required to spend the funds. Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) makes it possible to verify the inclusion of a transaction in a blockchain without verifying the entire blockchain. A SPV two-way peg scheme could work as follows: The locked Bitcoin are stored in an output that can only be spent if an SPV proof is provided that a corresponding number of tokens have been burnt on the sidechain.

#

Examples

Liquid Network is a federated sidechain, relying on the concept of strong federation. A strong federation consists of two independent entities: block signers and watchmen. Block signers maintain the consensus and advance the sidechain, while watchmen realize the cross-chain transactions by signing transactions on the mainchain using a multisignature scheme.

The members of the federation maintain the consensus of the sidechain by signing blocks in a round-robin fashion. The federation consists of large exchanges, financial institutions, and Bitcoin-focused companies but their identities are not public. Users trust that at least two-thirds of the federation is acting honestly to ensure security. Watchmen sign each block transferred between the mainchain and the sidechain on the mainchain using a multisignature scheme.

The sidechain Liquid is based on the Bitcoin codebase, however it has a 10x higher throughput due its block time of just one minute. Liquid supports the creation of on chain assets as well as enhanced privacy through confidential transactions. More info.

Rootstock (RSK) is a smart contract platform with a native token called Smart Bitcoin (RBTC) that is pegged 1:1 with Bitcoin (BTC) and is used to pay for gas when executing smart contracts on the RSK network. RSK is merge-mined with Bitcoin, meaning that RSK miners also mine Bitcoin but not vice versa.

RSK relies on a combination of a federated two-way peg and an SPV (Simplified Payment Verification) scheme. Users can send Bitcoin to the peg and they are issued RBTC on the RSK sidechain. Each transfer between the sidechain and the main chain requires a multi-signature by the RSK federation to complete the transferring process. Federation members use hardware security modules to protect their private keys and enforce transaction validation. More info

#

Evaluation

Both centralized and federation based sidechains have the disadvantage of introducing trusted third parties, arguably defeating the purpose of a blockchain solution. SPV based solutions have the advantage of being trustless, however users have to wait for lengthy confirmation periods. The second problem is that the consensus mechanism of the sidechain is typically less secure than Bitcoin's, making it the weakest link in the system and prone to attacks.

Trustlessness. Only for pure SPV based solutions.

Expressiveness. If the sidechain uses the account model.

Efficiency. No as the sidechain typically uses the account model.

#

Rollups

A rollup is similar to a sidechain but (a) the federation is replaced by a smart contract and (b) transaction data is stored on the main chain instead of a separate blockchain. The rollup can have its own transaction format independent from the main chain and we will refer to these transactions as L2 transactions.

To use a rollup, a user deposits funds to the rollup smart contract on the main chain. These funds can then be used in L2 transactions. To use the rollup, a user sends a L2 transaction to a designated user called aggregator. Periodically, the aggregator selects a batch of L2 transactions, creates a main chain transaction and publishes it. This main chain transaction contains the L2 transactions in compressed form and the hash of the new state. The rollup’s smart contract on the main chain assures the aggregator posted the hash of the correct new state. There are different ways that this check occurs, optimistically or using zero knowledge proofs, as discussed below. When users wish to redeem their deposit, they transact with the rollup’s smart contract on the main chain and receive funds equal to the amount of their balance on the L2.

#

Optimistic Rollups

In an optimistic rollup the aggregator posts the compressed L2 transactions and the hash of the new state to the main chain without any verification. A group of users called verifiers check that the new state matches the instructions in the L2 transactions. Verifiers can then publish a "fraud proof", claiming that the aggregator posted an incorrect hash.

To discourage aggregators and verifiers from acting maliciously, both the aggregator and verifier need to stake a bond. If the verifier can provide a valid fraud proof, the verifier earns half of the aggregator’s bond while the other half is burned (this is to prevent a scenario where a malicious aggregator tries to front-run an honest validator by publishing another fraud proof). If the fraud proof is invalid, the verifier gets fined.

#

Zero-knowledge Rollups

While optimistic rollups use fraud proofs, zero-knowledge (ZK) rollups, and validity rollups more generally, use validity proofs. Instead of allowing the aggregator to publish a transaction and then question it, in ZK rollups, the aggregator must prove that the state hash is the correct using a validity proof.

Similarly to optimistic rollups, an aggregator (sometimes called sequencer) evaluates L2 transactions and published compressed transaction data and the new state hash to the main chain. However they add a ZK proof that is evaluated by a smart contract on the main chain. The smart contract ensures that only correct executions are recorded on the main chain. In contrast to optimistic rollups, ZK rollups do not require second layer verifiers and there is no dispute resolution. This means transactions achieve finality rapidly; there is no extended period of time where verifiers can trigger a dispute phase.

The two most commonly used ZK proofs used for rollups are called SNARKs and STARKs. SNARKs are computationally efficient: the time needed to verify a SNARK grows slower than the time of the computation itself. However, they require a trusted setup. STARKs require no trusted setup, but require much more time for proof generation and verification.

#

Examples

BitVM is an optimistic rollup. Its primary purpose is facilitating trust minimized bridges between Bitcoin and other chains.

A federation of 1000 members engage in a trusted setup and users trust that at least 1 participant is honest, otherwise the federation can steal all funds. Peg-ins can be censored by any federation member as a peg in requires the collaboration of all federation members. In addition all federation members need to pre-sign 100 peg-out transactions each (100.000 transactions in total), therefore peg-ins only occur every 6 months.

There are 100 operators and users trust that at least one online operator is honest, otherwise the user can be prevented from pegging out. Operators must be able to front the money for a peg out for two weeks, so only well capitalized institutions can be operators. Withdraws can take months to give validators the chance to go through the challenge process. Any user can be a validator.

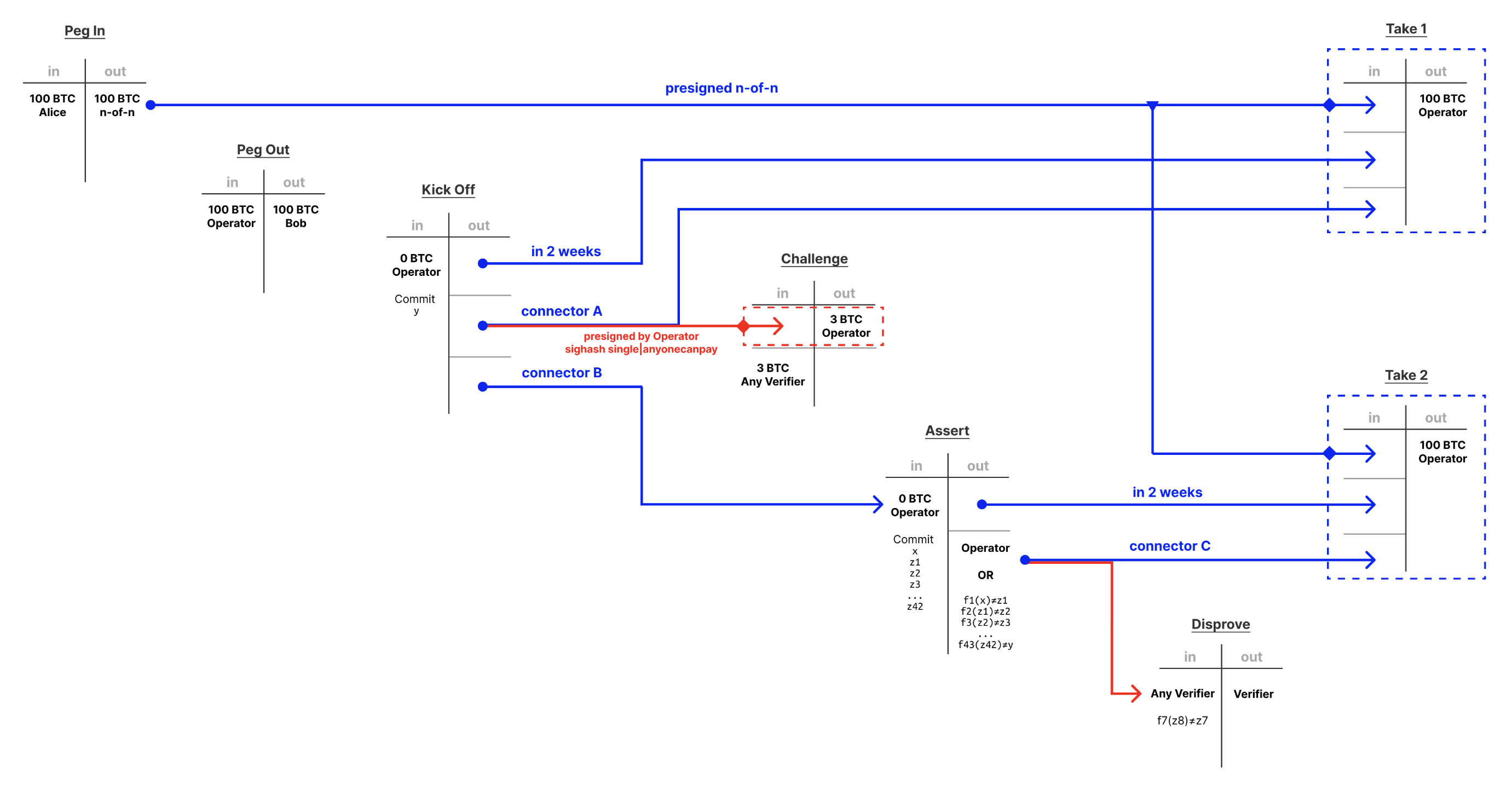

To "peg in", a user called Bob sends 100 Bitcoin to a n-of-n multisig address controlled by the federation. In exchange, the federation will issue Bob tokens on the destination blockchain. When Bob want's to "peg out", Bob signals his wish to the federation by burning tokens on the destination blockchain. Operators can front the 100 Bitcoin to Bob in a "Peg Out" transaction. The operator then broadcasts the "kick-off" transaction. If all goes well, and there is no dispute, the federation will broadcast the "Take 1" transaction that spends 100 Bitcoin to the operator.

In the case of a dispute, any validator will broadcast the "Challenge" transaction. Once this transaction is broadcast, the "Take 1" transaction cannot be spend anymore, as both transaction spend the same output (this is called a connector output). Once the "Challenge" transaction is broadcast the operator will broadcast the "Assert" transaction that breaks down the high level statement that the operator originally made, into smaller, easily disprovable statements. If any of these lower level statements are incorrect, any verifier can broadcast a "Disprove" transaction that points to the false statement by the operator. If no validator broadcasts a Disprove transaction, the operator can broadcast a "Take 2" transaction to regain control of the original 100 Bitcoin. More info here and here.

Todo. More info

Todo. More info

Todo. More info

#

Evaluation

Rollups rely on smart contracts on the main chain, therefore it is easier to make them trustless and practical on chains with strong native smart contract support like Ethereum. By understanding the properties of rollups on Ethereum, we can understand how rollups on Bitcoin can work in the best case.

On Ethereum rollups generally introduce trusted third parties, central points of failures, and lockup periods.

As building a validity proof requires heavy computations ZK rollups’ L2 fees are higher than optimistic rollups. Additionally, ZK rollup main chain transaction fees are higher as the validity proof needs to be validated on the main chain for every batch.

On the other hand, optimistic rollups have a period where verifiers have an opportunity to publish a fraud proof. Thus users need to wait (usually a week on Ethereum, on Bitcoin it will likely be longer) until their deposits can be withdrawn. In ZK-rollups, deposits could be withdrawn immediately, however in many cases users have to wait for 24h due to safety concerns. In most cases there is only one aggregator and a very small number of validators and users trust that they do not collude.

The Big-O notation is used in Computer Science to describe the upper bound of the runtime of an algorithm in terms of the size of its input. An algorithm is said to run in time O(f(n)) if for sufficiently large input sizes n, the algorithm's runtime will not exceed c * f(n) steps.

Prover Complexity refers to the computational complexity associated with generating a proof for a given computation. Verifier Complexity refers to the computational complexity associated with verifying the correctness of a proof for a given computation. The table below is obtained from here

#

Verifier complexity for SNARKs is O(1) meaning that the time to verify a computation can be take longer for small inputs but is faster (even constant) for large enough inputs. Verifier complexity for STARKs is O(\text{log}(n)^c) meaning that it can take much longer to verify a short computation but for very large computations verification is faster than computation.

Trustlessness. In optimistic rollups users trust that one honest validator is online at all times. STARKs are trustless, SNARKS are not.

Expressiveness. Depends on the expressiveness of the L2.

Efficiency. Depends on the efficiency of the L2.

#

Meta Protocols

A user of a meta protocol that wants to write smart contract data adds meta data to a transaction and sends it to the Bitcoin miners. Software that is specific to the protocol parses the meta data and computed smart contract data (like the number of tokens owned by a user) from it.

There are two basic types of meta protocols called block-order based and UTXO based. These two types result form two basic ways of viewing a UTXO based blockchains: as a list of transactions and as a graph of transactions.

#

Block-order based

The software for a block-order based protocol reads all transactions in the main chain in block-order to find transactions with meta data specific for that protocol. It will then interpret that sequence of meta data values as instructions and build up a data structure of smart contract data. The smart contract data will for example store which user owns which tokens.

We denote the set of transactions by T. We denote by V the set of smart contract data values where \{\} \in V denotes the empty value. We denote the set of sequences of values in a set X by X^*.

#

A block-order based meta protocol P consists of a function f: V \times T \rightarrow V. Let t_1 \ldots t_n \in T^* be the sequence of meta data values for P in the main chain in the order of their occurrence. Then P computes the smart contract data value f( \ldots f(f(\{\}, t_1), t_2) \ldots , t_n).

#

Example: BRC20

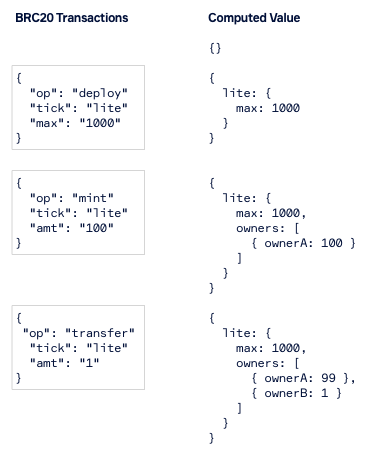

The BRC20 protocol is a protocol for fungible tokens.

The image on the right shows an example execution of the BRC20 protocol. The left column shows the meta data values and the column on the right shows the value that is computed after parsing each respective meta data value. The smart contract data value is initialized to the empty element \{\}. The first meta data value { op: deploy, ... } specifies the deployment of a fungible token called "lite" with a maximum supply of 1000. Once the BRC20 software parses this meta data value it updates its computed value to { lite: { max : 1000 }} as shown on the right. The next transaction contains a mining instruction and the software will update it's internal value accordingly as shown on the right. The bottom row shows a transaction shows a transfer transaction and the computed value that reflects that ownerB received one token from ownerA. The ownership of the assets is determined by the ownership of the outputs that contain the meta data. See here for more details.

#

Evaluation

Trustlessness. Yes.

Expressiveness. No, the existing block-order based protocols that we are aware of are single purpose only.

Efficiency. No, block order based protocols need to parse all transactions to compute a single value.

There are two other issues issues: Block-order based protocols cannot be real time as there is no indication in which order the transactions will occur on the mempool before a block is mined. Miners are incentivized to include transactions in an order that is advantageous to them. This is a common problem in Ethereum called "miner extracted value" (MEV).

#

UTXO based

Whereas block order based systems compute one global value from all transactions, UTXO based protocols compute a value for each output that is relevant to that protocol. The value computed for an output can usually depend on the meta data on that transaction and the valued computed for the inputs spent.

Let O be the set of outputs. A UTXO based protocol P is a function P: O \rightarrow V that map outputs to smart contract data values.

We will say that a protocol P is well designed if P(o) can be computed from the meta data on the transaction containing o and the values of the outputs spent by t. That is, there is a function f_P: O \times V^* \rightarrow V such that P(o) = f_P(o, P(o_1) \ldots P(o_n)) where o_1 \ldots o_n are the outputs spent by the transaction containing o.

#

We can see that all well designed UTXO based protocols are efficient: You can compute the value of an output by parsing "only" the transactions that are reachable form the transaction containing the output via the of the spending relation, potentially using multiple hops. This is still a large number of transactions in general, but for some values for example those on the outputs of a coinbase transaction can be computed from one transaction.

#

Example: Ordinals

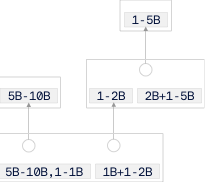

The ordinals protocol is a protocol for non-fungible token. It associates an integer with every satoshi and a list of integers with each output. The length of the list of integers is equal to the number of satoshis stored in the block. It does not require any meta data.

The ordinals algorithm computes the block rewards r_1, r_2, \ldots for every block in a chain. It then labels the output of the coinbase transaction of block i with the numbers ranging from r_0 + \ldots + r_{i-1} to r_0 + \ldots + r_i where r_0 = 0. To label the outputs of a transaction with inputs, the algorithm first determined the ordinal ranges of the outputs being spent and concatenates them. This array is used to label the outputs as follows: for each output, the algorithm will remove as many numbers from the array as the output has satoshis and assign that list of numbers to the output. The array will be sufficiently long as the number of satoshis spent by a transaction transaction must always be at least the number of satoshis in the output. This presentation is slightly simplified as it does not take fees into account, for details see here.

We can see an example in the picture. The top transaction is the coinbase transaction of the first block. As the output of this transaction contains 5 Billion satoshis (= 50 Bitcoin) this output is labelled with the numbers 1, 2, \ldots 5.000.000.000. The transaction below spends that output and contains two outputs with 20 and 30 Bitcoin. The first of these outputs is labelled with the numbers 1, 2, \ldots 2.000.000.000 and the second with 2.000.000.001 \ldots 5.000.000.000. You can find more information here.

Trustlessness. Yes.

Expressiveness. No.

Efficiency. Yes.

#

Example: Runes

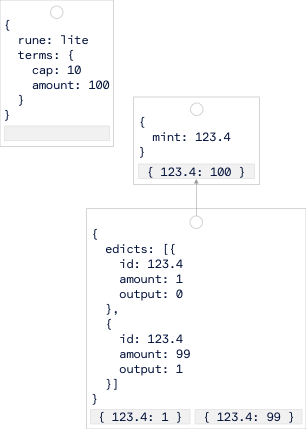

The runes protocol is a protocol for fungible tokens. Its smart contract data values are key value pairs where keys are token ids and its values are numbers. The meta data values are an efficient encoding of nested json objects.

There are distinct kinds of meta data values: "etchings" are used to deploy tokens, they can specify for example how many times a token is mined through the cap key and the number of tokens created in each mint via a key called amount. Minting instruction specify a token id (encoded as <block-number>.<offset>). "Edicts" transfer the tokens spent by the inputs into the outputs. A transfer transaction contains a list of edicts, each of which transfers the token id to transfer, the amount, and the output number. The meta-data is encoded into an array of integers which is stored in the op-return.

The picture shows an etching that deploys a new fungible token called "lite" that can be minted 10 times, creating 100 tokens on every mint. This transaction is assumed to be the 4th transaction in block 123. The second transaction show mints 100 tokens, the third transaction transfers the minted tokens into two outputs with one and 99 tokens each. You can find more information in the ordinals docs.

Trustlessness. Yes.

Expressiveness. No.

Efficiency. Yes.

#

Example: Bitcoin Computer

This Bitcoin Computer is a general purpose meta protocol, meaning that it can express all computable smart contracts. The smart contract data values are arbitrarily nested JavaScript objects. The meta data values contain mostly JavaScript expressions.

There are two types of transactions: "modules" contain JavaScript (ES6) modules. All other transactions contain a JavaScript expression, a "blockchain environment" that associated (free) variables in the expressions with input numbers, and an optional "module specifier" containing a transaction id. In order to compute the value of an output, the Bitcoin Computer software

- imports the module from the transaction referred to

- computes the values for the outputs being spent and then substitutes these values for the free variables in the expressions as designated by the blockchain environment

- evaluate the expression with the substitution applied in the scope of the module

The picture shows the deployment, minting, and sending a non fungible token and a non fungible token. For more details see the rest of the documentation.

Trustlessness. Yes.

Expressiveness. Yes.

Efficiency. Yes.

#

Sources

[1] SoK: Applications of Sketches and Rollups in Blockchain Networks, Arad Kotzer, Daniel Gandelman and Ori Rottenstreich; Technion, Florida State University

[2] Blockchain Scaling Using Rollups: A Comprehensive Survey, Louis Tremblay Thibault, Tom Sarry, and Abdelhakim Senhaji Hafid; Montreal

[3] SoK: unraveling Bitcoin smart contracts, Nicola Atzei, Massimo Bartoletti, Tiziana Cimoli, Stefano Lande, Roberto Zunino; Cagliari, Trento

[4] Beyond Bitcoin: A Review Study on the Diverse Future of Cryptocurrency, Mohammed Faez Hasan, University of Kerbala

[5] BitML: A Calculus for Bitcoin Smart Contracts, Massimo Bartoletti, Roberto Zunino; Cagliari, Trento

[6] An Overview of Smart Contract and Use cases in Blockchain Technology, Bhabendu Kumar Mohanta, Soumyashree S Panda, Debasish Jena; IIIT Bhubaneswar

[7] Layer 2 Blockchain Scaling: a Survey, Cosimo Sguanci, Roberto Spatafora, Andrea Mario Vergani; Polytechnico Milano

[8] A Rollup Comparison Framework, Jan Gorzny, Martin Derka; Zircuit

[9] SoK: Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

[10] SoK: Communication Across Distributed Ledgers

[11] Colored Coins whitepaper, Yoni Assia, Vitalik Buterin, liorhakiLior, Meni Rosenfeld, Rotem Lev

[12] Exploring Blockchains Interoperability: A Systematic Survey

[13] bitcoinlayers.org

[14] bitcoinrollups.io

[15] Hiro Blog

[16] Validity Rollupsvalidity_rollups_on_bitcoin.md